The Day Our Own Queries DoS’ed Us: Inside Zalando Search

Once upon a time, during a normal Sunday, our team ran into an unexpected challenge: an Elasticsearch cluster that suddenly became sluggish and unresponsive due to a self-inflicted Denial of Service (DoS) attack (of course we didn't know it at the time). This is the story of how we identified, mitigated, and learned from this incident.

Who We Are

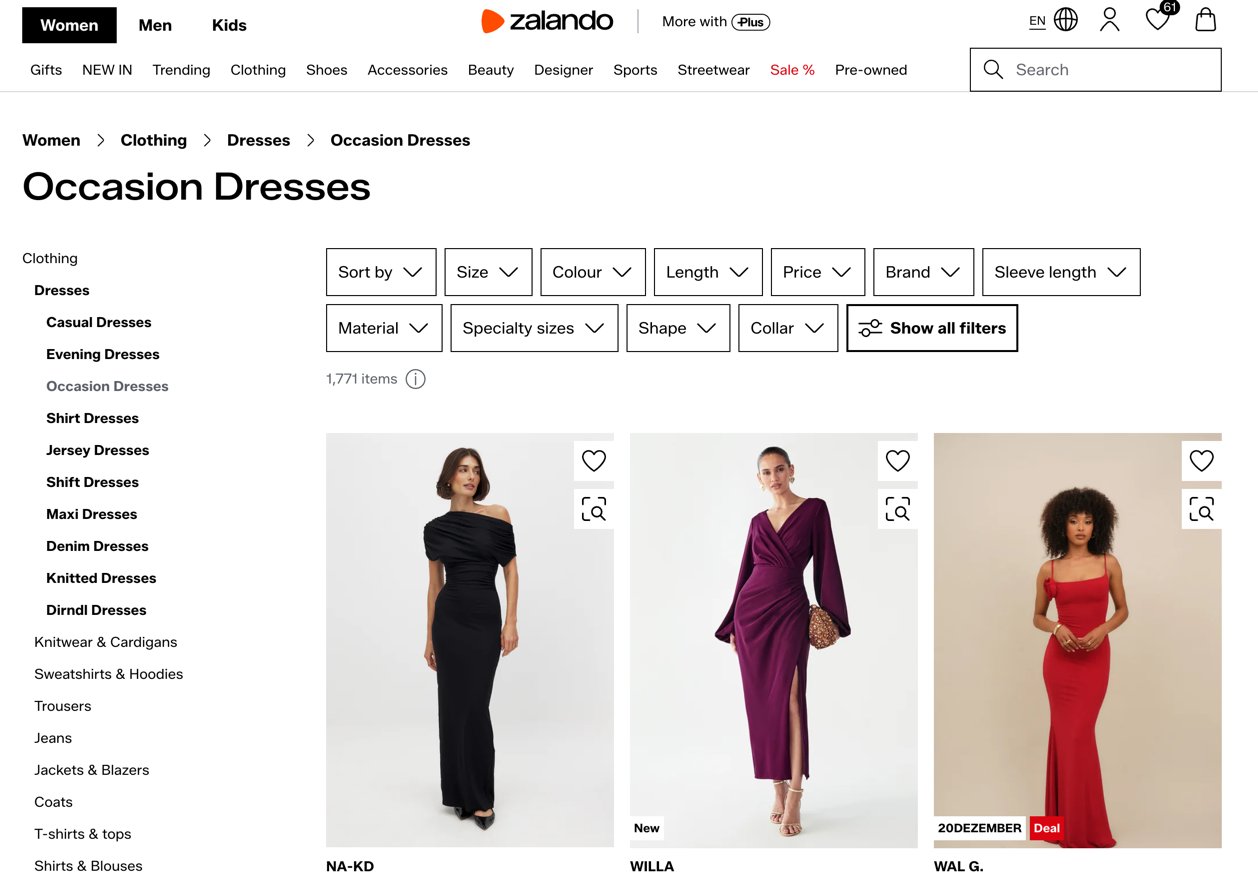

We are part of Zalando’s Search & Browse team, responsible for maintaining and optimizing the catalog and full-text search backends that power millions of user requests every single day. Our systems serve multiple catalog domains and experiences – from the core catalog to the Designer experience and our full-text search – and they also feed newer interfaces like Zalando Assistant, which depends on us to fetch and recommend products in real time.

When everything is healthy, the experience feels effortless. Customers can search, filter, and explore the catalog, ask Zalando Assistant for ideas and instantly see relevant products. At the same time, our brand partners’ promotions, campaigns, and sponsored placements are delivered as planned, reaching the right users at the right moment.

But when catalog search is slow or down, the impact is immediate and far-reaching. Customers suddenly can’t find what they want, filters and discovery flows break, and Zalando Assistant simply can’t fetch products to show. Partner campaigns underperform or effectively go dark, meaning money, planning, and trust are burned in real time. Negative reviews, customer complaints, and internal escalations start popping up across channels as frustration grows.

In short: when catalog search is degraded, it’s not “just” a tech issue. It hits customers, partners, campaigns, and Zalando’s reputation all at once. It’s a big deal. A very, very big deal.

Anthology of the System Under High Load

From the outside, “search is slow” looks like a single symptom. In reality, it flows through several layers, each doing its own work and adding its own pressure under load.

At the bottom, we have Base Search, an Elasticsearch cluster that provides initial candidates using both classic lexical matching and vector search. On top of that sits our full‑text search query builder Named Entity Recognition (NER) system, which takes the raw user intent (query text, user filters). Based on recognized entities it promotes implicit filters. Filters could be applied to shrink or expand results. NER system builds an Elasticsearch query and attaches metadata indicating whether the result set looks sparse and might require expansion using our newer neural matching system.

NER system also queries the Base Search to acquire product counts to understand how many products match different filter combinations and to decide whether we can safely narrow the search with extra filters without risking “zero results”.

Above that, the Catalog API, one of our presentation layers, coordinates everything that has to happen for a single “search” in the app:

- It fans out a request into several queries to Base Search.

- It is integrated with our A/B testing framework, so different users or cohorts may trigger slightly different query shapes.

- It owns the “final redirect” decisions – for example, whether a query should land on a generic search result page or on dedicated landing pages.

Each layer includes its own caching:

- The query builder and Catalog API cache popular queries and filter combinations.

- In Elasticsearch, coordinator nodes are placed on separate machines and provide another caching layer for search results and aggregations.

- The Base Search Elasticsearch cluster itself is wrapped by a lightweight Search API component - another presentation layer.

The Search API in turn integrates with other components:

- Algorithm Gateway enriches results with user actions data and re‑ranked using the rules engine and our personalization and relevance ML models.

- Promotions bidding service, it blends sponsored content with organic results.

For every search, the Catalog API issues a separate call to fetch the filters (facets) for that query: brand, size, color, price bucket, etc. These are aggregation‑heavy queries by design and stress Elasticsearch differently than “plain” document retrieval. Under normal conditions, they are well‑behaved and benefit from caching at multiple layers.

Under high load, however, a pathological pattern in just this one type of query – facets – can put disproportionate pressure on Elasticsearch and its coordinator nodes, while everything above simply sees “search is slow” and “filters are broken”.

The Incident

On a seemingly ordinary Sunday, our Elasticsearch cluster began to exhibit signs of distress. Queries that usually took milliseconds were now dragging on for seconds, and some requests were timing out altogether. Users started seeing empty result pages, or pages with just a few items. These are some immediate customer feedback examples in our 1* App Reviews from users experiencing problems during the incident:

- "App barely functional. Search and filter function not usable. App therefore unusable."

- "Each filter shows 0 results found."

- "Filters are buggy, constantly show that no articles were found or are suddenly no longer displayed."

The initial alerts came from our monitoring systems, which indicated a spike in response times and error rates. The Search on-call responder was paged.

The responder quickly jumped into action, diving into the logs and metrics to identify the root cause. After initial investigation, it became clear that the Elasticsearch cluster CPU was spiking. No recent deployments or configuration changes had been made. No sudden increase in client traffic was observed; the same was true for the write load. The cluster was simply overwhelmed for no apparent reason.

The issue was only affecting one of our Elasticsearch clusters, the one responsible for serving two of the largest markets. Other clusters were functioning normally, proving that our market grouping isolation worked as designed. That was a small relief, but it was still unclear what was different about this particular cluster, since they were all configured similarly.

Immediate Actions Taken

The on-call responder, leveraging our incident playbooks, initiated a series of immediate actions to stabilize the situation:

- Applying longer cache expiration times to reduce load on the cluster;

- Disabling non-critical requests that could be consuming resources;

- Applying lower cluster-wide query termination thresholds to prevent long-running queries from hogging resources;

- Scaling out the coordinator nodes to distribute the query load more effectively;

- Scaling out data nodes to increase the cluster's capacity.

These actions, however, have not provided even a temporary relief. The cluster remained under significant strain, and the root cause of the issue was still unclear. All these actions took time to be applied and verified, and by that time, several other team members joined the on-call responder to provide help. But the situation was still critical.

The Markets

As mentioned above, the issue was predominantly affecting two markets with larger product catalogs. As an experiment, it was decided to split the markets into two separate clusters, to see if that would help alleviate the load or isolate the problem. If the relocated market would not have issues, it could indicate that the problem was related to the specific queries or infrastructure associated with the remaining market.

The market split would be done by using the node allocation settings in Elasticsearch, which allow for controlling which nodes hold which shards. By specifying different node groups for the two markets, the data could be effectively split.

Additional Load Shedding: Making the Cluster Breathe Again

To give the cluster some air, we rolled out additional load shedding measures in parallel. On the Elasticsearch side, we first reduced the number of shard replicas, so there would be fewer shards to relocate once we started splitting the markets. We then throttled ingestion all the way down to a full stop, ensuring no new data was being written while the cluster was already struggling and while shards were being moved. Finally, we split the markets: the smaller of the two markets was relocated to a new Elasticsearch cluster, while the larger one stayed on the original one.

At the same time, on the application side, the presentation layers were used as a control plane to reduce load on downstream systems: we turned off non‑critical calls, reduced the number of parallel queries per request, and increased cache effectiveness for hot queries and filter combinations. Our search steering configuration also played a key role here: we lowered the load generated by search by sampling fewer requests into some heavier ML model integrations and promotion‑enrichment flows, falling back to simpler ranking where needed.

New Investigation and Finally, Root Cause

Having split the two markets into dedicated clusters, we have proven that the issue originated from queries targeting a single market. The team began a more in-depth investigation into the queries being executed on the affected cluster. It was discovered that Elasticsearch was under heavy load because of a specific type of queries: faceting queries that were performing aggregations. An attempt to get sample slow queries was made, but the cluster was too overloaded to respond to the request. With the cluster being in distress, all queries became slow and the tasks index was overflowing with long-running queries. Also, many tasks were being rejected before they could be completed or even accepted, because the queue just maxed out.

Before the Dawn: Cluster Recovery

At some point in the evening, the cluster started to recover. The CPU usage began to drop, and the query response times improved. The cluster returned to a stable state. However, the root cause of the issue was still not understood, so the team continued to investigate. No one was satisfied with just having the cluster back up; they needed to know what had caused the problem in the first place. The incident could resurface at any time if the underlying issue was not addressed.

After some more digging, an exploratory analysis of traces in a Lightstep notebook detected an unusual traffic pattern from one of our internal applications. Further investigation revealed that the application was sending 50 times more queries than usual, and it matched the incident timeline exactly.

The Revelation

These queries were not typical user queries. They were faceting queries that were requesting huge aggregations on very high cardinality fields, specifically on the SKU, which is a unique product ID. These types of queries are extremely resource-intensive, as they require Elasticsearch to process and aggregate a vast amount of data. Also, they aren't making any sense from a business perspective, as faceting on unique identifiers does not provide any meaningful insights.

It was later discovered that the root cause of the issue was a self-inflicted Denial of Service (DoS) attack. As a result of a maintenance workload coupled with a bug in the processing logic of the application, the internal client application was sending a small, but sufficient number of parallel overwhelming faceting queries to the Elasticsearch cluster.

Why wasn't this detected earlier?

- Because the queries were legitimate in terms of syntax and structure. They were valid Elasticsearch queries, but they were being used in a way that was not intended or expected. A workload meant to be executed seldom, triggered by business users, was getting triggered by the maintenance procedure in an automated fashion.

- Because the service sending the queries was an internal application, a legit one, and not new.

- Because the load was very low in terms of volume. Elasticsearch is usually handling thousands of requests per second. This service was only sending 20-100 requests per second, which in terms of normal Elasticsearch load was peanuts. We did have per-client traffic monitoring, but the load from this service was just too low to attract any attention; it was simply flying under the radar, dwarfed by the traffic from other services triggering thousands of requests per second.

- Because the slow queries, while being monitored, were not being analyzed in depth. The team was focused on the overall cluster health and performance metrics, and the slow queries were just a symptom of the larger issue.

- Because the slow queries didn't have any specific tags or identifiers that would link them to the client application. They were just faceting queries, indistinguishable from any other faceting queries that might be executed by legitimate users.

The key question here is why the faceting queries on high cardinality fields caused an overload of the cluster.

Some theory on Elasticsearch DoS via Faceting Queries on High Cardinality Fields

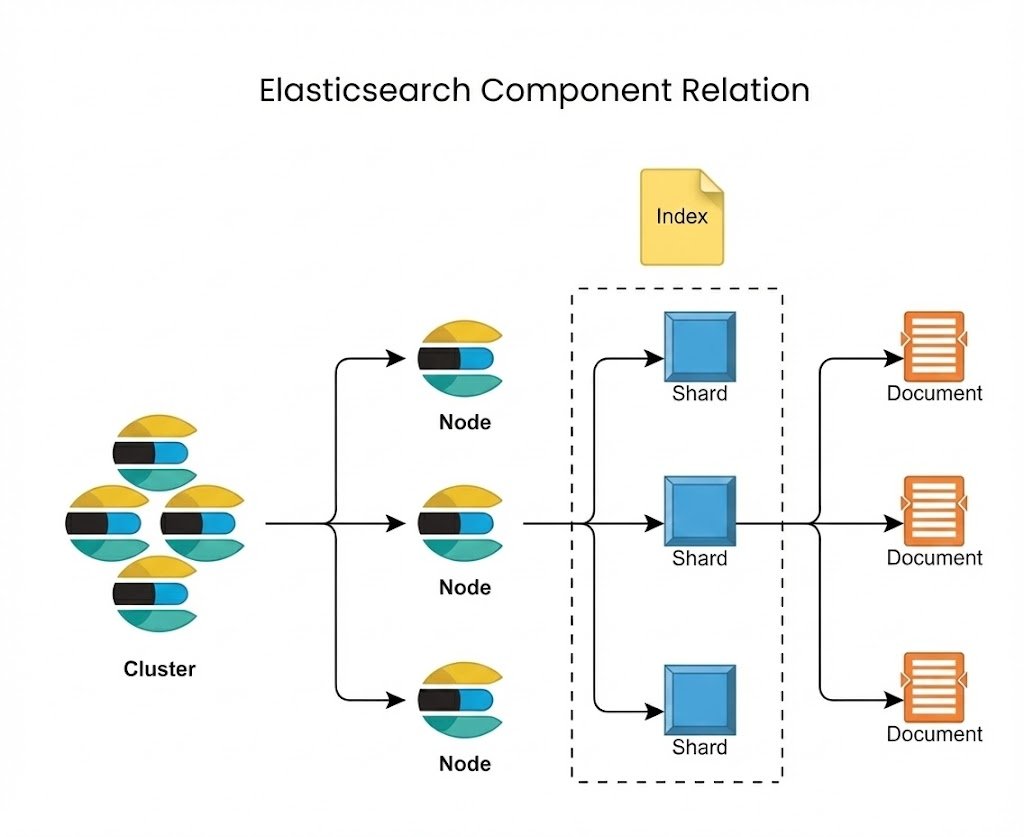

When you send a faceting query to Elasticsearch, you’re not just hitting “one big index”. Internally, the request follows a scatter/gather path. A coordinating node (in our case, we had dedicated coordinator nodes) takes the incoming search request, scatters it to all relevant shard copies, and then gathers the partial results back, reducing them into a single response. Shard selection is influenced by Adaptive Replica Selection, which tries to pick the “best” shard copy based on past response times and the node’s search thread‑pool queue size. For aggregations, the coordinator also performs partial reductions in batches instead of waiting for all shards to finish at once, and Elasticsearch enforces soft guardrails like search.max_buckets to prevent a single request from creating an unbounded number of aggregation buckets. On top of that, we also use index‑level max_result_window settings to make sure no single request can ask for a “scroll the universe”‑sized result set.

All of this work runs on several dedicated search thread pools. The search pool handles per‑shard query and aggregation execution; if too many shard‑level operations run at once, this queue fills up and Elasticsearch starts rejecting requests. The search_coordination pool takes care of the lighter orchestration work on the coordinating node: merging partial results, running reductions, and preparing the final response. Starting with 8.12, Elasticsearch also introduces a search_worker pool used by parallel collectors for some aggregation and query types, where work inside a shard can be fanned out across segments (“slices”) to reduce latency. Our incident, however, was driven by high‑cardinality terms aggregations, which are not executed with those parallel collectors; they simply ran as very heavy work on the searchpool, consuming a lot of CPU and memory. A small number of such pathological facet queries was enough to keep the cluster “hot” and to starve normal traffic, which is exactly what a DoS looks like in practice.

Follow-up Actions and Lessons Learned

This incident was a wake-up call for our team. It highlighted the difficulty of investigating performance issues in Elasticsearch, especially when the root cause is not immediately apparent. It also underscored the importance of understanding the behavior of internal applications and their potential impact on shared infrastructure.

From this incident, we learned several valuable lessons:

- We need to think how we can split and isolate workloads better, applying rate limiting based on the type of the client traffic. Not all clients should be equal, and we might need a more granular access control.

- The importance of thorough monitoring and logging. We extended the slow query logging to capture more details about the queries being executed, including client identifiers via the X-Opaque-Id request header.

- Based on that, we also extended the dashboards to monitor per-client slow query rates, and specifically aggregating queries and the aggregation sizes.

- We introduced application-side query limiting with dynamically adjustable thresholds, to prevent queries that would try to scan or aggregate too much data.

- We improved our playbooks and runbooks for Elasticsearch incidents, providing detailed steps for investigation and mitigation, for distinguishing between high read load vs. write load, and for rate limiting or blocking misbehaving clients.

- We introduced new runbooks on applying cluster-wide settings like search.max_buckets to limit the size of aggregations on the whole cluster at once.

But one of the most important lessons learned requires asking the same question again.

Why wasn’t this detected earlier? Because we were looking for a horse.

You know that old saying about the horse and the zebra? When you hear hoofbeats, think of horses, not zebras. Because horses are common, and zebras are rare.

But in our case, it happened to be a zebra.

We were looking for common causes of Elasticsearch performance issues: high read load, high write load, misconfigurations, infrastructure issues. We were not expecting a self-inflicted DoS attack from an internal application.

So keep in mind: sometimes, when you hear hoofbeats, it might just be a zebra.

You don't see them often, but when you do, they can be quite a spectacle.

Useful Links

- max_buckets setting documentation

- Elasticsearch Slow Log documentation

- Documentation about tasks API mentioning X-Opaque-Id request header

- Medium article by Andrei Baptista on debugging slow queries using X-Opaque-Id

- Apache Lucene deep dive: Inverted Index, Search, Replication

We're hiring! Do you like working in an ever evolving organization such as Zalando? Consider joining our teams as a Backend Engineer!